Inflation erodes the purchasing power of

money. Even with a low annual inflation rate of

2 per cent (the midpoint of the Bank of Canada’s

1 to 3 per cent target range for inflation since 1995),

a dollar will lose half of its purchasing power in

approximately 35 years. When the consumer price

index (CPI) is used to measure inflation, the average

annual rate of inflation in Canada since 1914 is

3.2 per cent. Thus, the Canadian dollar lost more

than 94 per cent of its value between 1914 and

2005 (Chart A1). Alternatively, one dollar in 1914

would have the purchasing power of $17.75 in

2005 dollars.1

While consumer price data prior to 1914

are unavailable, a broader measure of inflation, the

gross domestic product (GDP) deflator, is available

back to 1870 (Leacy 1983).

While the CPI and GDP

deflator can diverge, they tend to move together

over time. Since 1870, with annual GDP inflation

averaging 3.6 per cent, the Canadian dollar has lost

more than 96 per cent of its value. Again, this is

equivalent to saying one Canadian dollar in 1870

would have the purchasing power of roughly $26.70

in today’s money.

Periods of high inflation include the early

years of the twentieth century, when major

infrastructure projects in Canada were financed by

large inflows of foreign capital, and the years during

and immediately following the two world

wars, owing to the cost of the war effort and

Appendix A

Purchasing Power of the Canadian Dollar

1. The Bank of Canada has an inflation calculator on its website (www.bankofcanada.ca) that shows changes in the costs of a fixed basket of consumer

purchases from 1914 to the present.

Chart A1

Purchasing Power of the Canadian Dollar

1914 = 100

Source: Leacy (1983)

demobilization. More recently, high inflation was

experienced during the 1970-80s, owing to the oil

crises and policy errors (Chart A2).

In contrast, prices fell during the early

1920s, when Canada experienced deflation on its

return to the gold standard and during the

Great Depression of the 1930s. Prices also fell

episodically during the last decades of the

nineteenth century.

To provide a different perspective on the

purchasing power of the Canadian dollar, Table A1

lists indicative prices of selected food staples since

1900. As can be seen, the cost of a pound of butter

has risen from about 25 cents at the beginning of

the twentieth century to about $4.00 today. At the

same time, a labourer in 1901 would have earned

14 to 15 cents an hour in Halifax or Montréal

and 23 cents in Toronto.2 In contrast, the 2005

A History of the Canadian Dollar 89

Chart A2

Inflation in Canada

Year-over-year percentage change

Source: Leacy (1983)

2. Leacy (1983), “Hourly wage rates in selected building trades by city,” series E248–267. The earliest available data point for a western province is 1906.

At that time, the average labourer in Vancouver would earn 35 cents per hour.

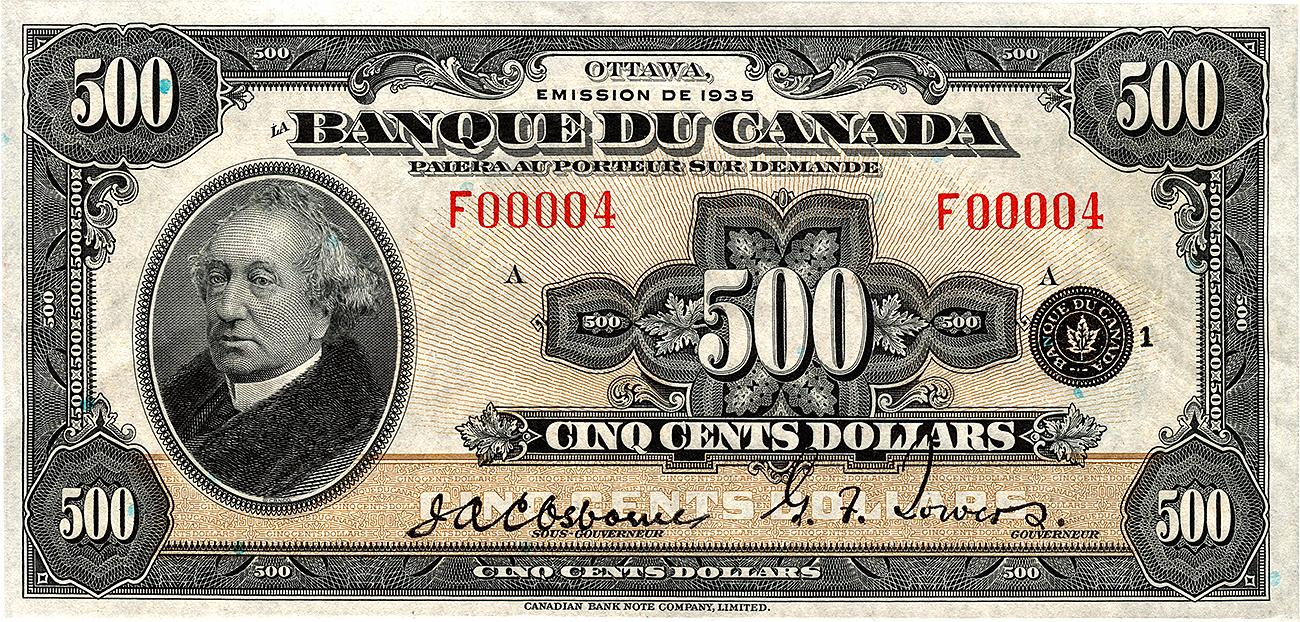

Image protected by copyright

90 A History of the Canadian Dollar

minimum wage in Canada ranged from $6.30 an

hour in New Brunswick to $8.00 an hour in

British Columbia.

In 1905, the average production worker in

a factory earned $375 per year, while the average

supervisory and office employee earned $846.3 In

2004, the average annual income of a person

working in the manufacturing sector was $42,713.

The average manager’s salary was $70,470.4

A significant portion of the increase in salaries

since the early 1900s would reflect the impact of

inflation.

Other currencies also lost domestic

purchasing power over time owing to inflation. In

Chart A3, one can see that while Canada’s accumulative inflation performance has been significantly

better than that of the United Kingdom over the

period since 1914, our performance has been largely

the same as that of the United States. Only in the

last ten years or so, has Canada averaged a lower

rate of inflation than the United States.

In terms of gold, the Canadian dollar has

depreciated markedly over the years, much of this

occurring since the early 1970s. One ounce of gold

was worth $20.67 in 1854 when the Currency Act

was passed in the Province of Canada, fixing the

Canadian dollar at par with the U.S.-dollar, equivalent to 23.22 grains of gold. In 1933, the statutory

price of gold in Canada was the same, $20.67 per

3. Leacy (1983), “Annual earnings in manufacturing industries, production and other workers,” series E41–48.

4. Statistics Canada, Manufacturing: Trades, Transport and Equipment Operators & Related Occupations and Manufacturing: Management Occupations.

Table A1

Indicative Prices of Selected Food Staples, December (dollars)

Beef (sirloin) per lb.

Bread (loaf)

Butter (one lb.)

Eggs (one dozen)

Milk (quart)

1900

0.14

0.04

0.26

0.26

0.06

1914

0.24

0.05

0.35

0.45

0.10

1929

0.35

0.08

0.48

0.65

0.13

1933

0.19

0.06

0.26

0.45

0.10

1945

0.43

0.07

0.40

0.56

0.10

1955

0.80

0.13

0.64

0.70

0.21

1965

1.10

0.18

0.63

0.64

0.26

1975

2.34

0.43

1.11

0.92

0.43

1985*

3.81

1.00

2.51

1.34

1.12

1995

5.05

1.30

2.87

1.63

1.46

2005**

6.99

1.79

4.01

2.22

1.97

Source: The Labour Gazette, Dominion Bureau of Statistics, Statistics Canada

*October

**June

ounce.

The official U.S.-dollar price of gold was

raised to US$35 per ounce (roughly the same in

Canadian dollars) on 31 January 1934 when

President Roosevelt’s administration took steps to

reflate the U.S. economy during the Great

Depression. The US$35 per ounce price remained

fixed until 15 August 1971 when President Nixon

broke the link between the U.S. dollar and gold. In

Canadian dollars, one ounce of gold was worth

about $35.40 on that date. In late October 2005,

the market price of an ounce of gold stood at

roughly $550 in Canadian funds (or about

US$465).5 In other words, the Canadian dollar has

lost about 96 per cent of its value in terms of gold

since 1933, with much of this occurring since

August 1971, while the U.S. dollar has lost roughly

95 per cent of its value.

Periods of rapid inflation, as well as

episodes of significant deflation,

in Canada over the

past century or more underscore the importance of

the Bank of Canada’s objective of maintaining low,

stable, and predictable inflation. If an economy is

to perform well, its citizens must have confidence

that the value of the money they use is broadly

stable—that is to say subject to neither chronic

inflation or deflation. Both inflation and deflation

create uncertainty about the future and can have a

significant negative impact on the economy. Their

effects also do not fall equally on the population.

Unexpected inflation or deflation redistributes

income and wealth, between borrowers and lenders,

and between generations. Consequently, to avoid

the burden that inflation or deflation imposes on

an economy, it is important for a central bank to

pursue a monetary policy that is firmly focused on

achieving and maintaining price stability